On Arab cartoons and western hypocrisy

Ali Ferzat, drawn as St George killing the dragon, aka Assad the lion, with his sharp pen, by Palestinian cartoonist Ramzi Taweel

The Arab world loves satirical cartoons. BBC Arabic’s current affairs TV show 7 Days even used to devoted the final ten minutes of each programme to a discussion of the week’s cartoons from the Arab press. So what is all this fuss about the Charlie Hebdo cartoons?

The Koran explicitly tells Muslims how to react when their religion is mocked, in verse 140 of Sura Al-Nisa:

“God has sent down upon you a commandment in the Book, that if you hear disbelievers denying and mocking the verses of God, do not sit with them until they change to a different topic, otherwise you will become like them.”

The Koran, regarded by all Muslims as the word of God, is not open to dispute.

Why therefore does the mockery of Islam using cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad provoke such extreme reactions across the Islamic world?

The obvious answer lies in orthodox Islam’s position on religious figural art, whereby images of God, the Prophet Muhammad and other prophets, though not explicitly forbidden in the Koran, are not permitted according to longstanding tradition: only God is permitted to create humans, not humans themselves. That is seen as idolatry and therefore blasphemous. Traditional religious Islamic art is therefore overwhelmingly composed of geometric shapes and designs through which it seeks to represent God’s infinity, beauty, all-embracing nature and much more.

But there is another answer, behind the obvious, which has its roots, not in religion, but in socio-economic frustration and the perceived hypocrisy of the West.

All too often, when westerners look East, they see nothing but the chaos of the Middle East apparently created by Islamic extremism. A few, looking more closely, see the socio-economic inequalities fuelled by the rise of greedy dictators and their equally greedy cronies. They may even see how the rise in literacy across the region has led, not to better opportunities for employment, but to a massive dissatisfaction with the status quo among the under 30s who account for at least 60% of the population. Few realise that even in Saudi Arabia 60% are under 21 and far from rich.

Very rarely do westerners acknowledge their own governments’ role in creating the conditions for such chaos to flourish; in the creation of artificial states whose boundaries were drawn to suit western political and economic interests; in the creation of mandates whose remits were supposedly to protect and lead local populations to independence after World War I, but which in practice exploited them and set the various religious groupings against each other, sometimes in an expressly ‘divide and rule’ policy; and last but not least, in the creation of the state of Israel imposed on existing local populations without consultation.

When Muslims look West, they in turn see extreme, and in their eyes often hypocritical, reactions. Why does the West make so much fuss over the death of 17 people in France, four of whom were Jews, when over 200,000 Arab lives have been lost in Syria to apparent western indifference? Why does the execution of four western hostages trigger a massive wave of outrage, when the earlier execution of hundreds of Muslims by ISIS inside Syria and Iraq drew no reaction? Why does the plight of the Yezidi minority, escaping up Mt Sinjar in Iraq, attract worldwide attention and lead to US air strikes, when indigenous Muslims have already been killed in their thousands by ISIS?

Then on 19 January British Communities Secretary Eric Pickles sent a letter to 1,100 imams across Britain which, though well-intentioned, clumsily implied blame on the Muslim community for allowing Islamic extremism to flourish, as if it were in some way their fault and responsibility. The letter did not acknowledge that such a global phenomenon cannot be pinned on one community, that it is spread more than anything by savvy propaganda on the internet and social media.

Tragically, such faux-pas feed into a western perception that Islam cannot take criticism, and into a Muslim perception that the West is always setting itself up above Islam, taking the moral high ground. The many instances of Christian and Jewish extremism across history are somehow seen differently by their own adherents, as excusable reactions to unreasonable provocation. Guantanamo Bay sums it up. This is why the West’s ‘holier than thou’ approach often leads to accusations of hypocrisy from inside the Islamic world.

A recent slogan tweeted by the Kafranbel activists inside Syria gave their balanced reaction to the Charlie Hedbo massacres and the subsequent adulation across the West of the satirical magazine via the ‘Je suis Charlie’ campaign:

“Magazines’ Self-Glory should be built neither by mocking religions nor by their employees’ skulls. Islam has nothing to do with terrorism.”

Kafranbel’s own media centre satirising Bashar al-Assad, and its Radio Fresh broadcasting outlet was recently closed down by Jabhat an-Nusra extremists, on the pretext of it being against Islam: at the same time they closed down the Kafranbel Women’s Centre where local women trained as hairdressers, nurses and seamstresses, telling them they would be beheaded if they returned. The real reason for the closure was that the extremist group could not cope with being mocked, like all dictatorial regimes round the world. The widely circulated hashtag #We are all Hadi against Nusra (Hadi Al-Abdullah was the Kafranbel activist attacked by Al-Nusra) proved that Muslims will freely criticise other Muslims when necessary.

Kafranbel cartoon on ISIS v Free speech with a jihadi shooting the microphone of Radio Fresh at the Kafranbel Media Centre, by Iman

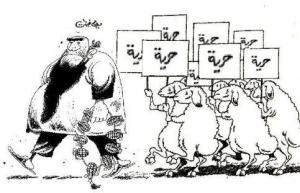

Satire of political leaders has long been popular in the Arab world, much to the chagrin of autocratic dictators. Egypt’s former president Muhammad Morsi hated being mocked by the ultra-popular comic satirist Bassem Youssef on TV. The current President Al-Sisi was equally unable to handle it, and Youssef’s slick show, modeled on that of American comedian Jon Stewart, went off air.

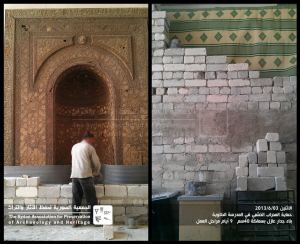

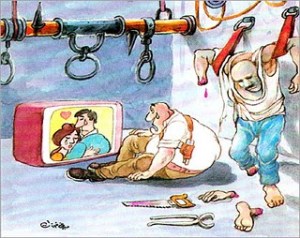

The Arab world’s most famous cartoonist Ali Ferzat was allowed in 2000 to set up a satirical magazine called Ad-Domari, The Lamplighter, in Syria, the first such magazine since the Ba’athists took power there in 1963. The new president, Bashar al-Assad, had been his friend and encouraged him during what was called ‘The Damascus Spring’. Three years later, the magazine was closed down for its irreverent cartoons against the Syrian regime, and in 2011 Ali Ferzat was beaten up on a Damascus street, his hands broken to punish his satirical cartoons against his former friend.

The singer Ibrahim al-Qashoush who wrote a popular anti-regime song was found in the river Orontes with his vocal chords cut out.

Torturers inside Assad’s prisons were known to force detainees to pray to a picture of Bashar and recite: “There is no God but Bashar”.

Defending free speech is easy if you like what is being said. But many Muslims feel damaged by the Charlie Hedbo media circus, misunderstood and unfairly vilified by the West. Islam’s absence of a conventional hierarchy also makes it difficult for moderate Muslims, especially Sunnis who account for about 85% of Muslims worldwide, to have a unified voice. While the minority Shia, largely found in Iran and Iraq, look to a handful of Grand Ayatollahs to guide them, Sunnis have no Pope or head of the church equivalent. No one Sunni group can speak for another and there are at least four main Sunni schools of law, each with their own theologians.

The West fears what it does not understand. But it must not allow distorted views of Islam’s nature to take hold. In the past, in its foreign interventions in the Arab world, the West has been driven by self-interest, despite its rhetoric to the contrary. Its own economic ambitions have been paramount, leading it to exploit the Middle East’s strategic location and natural resources.

If Western countries could honestly declare that their actions will in future also consider the interests of local populations, it might be a first step towards healing the misunderstandings which have led to so many of the region’s seemingly intractable problems. Respect between the West and Islam is essential.

Cartoon of Ali Ferzat fighting with his pen against oppression, by Matt Wuerker

Mount Qassioun, seen across the rooftops of Damascus

Mount Qassioun, seen across the rooftops of Damascus A blacksmith made a new metal door to cover the smashed antique one.

A blacksmith made a new metal door to cover the smashed antique one. Checkpoints and road blocks, such as this one in Yusuf al-Azma Square, are a common sight

Checkpoints and road blocks, such as this one in Yusuf al-Azma Square, are a common sight

![Prophetic 2007 poster of Bashar in Damascus' Hijaz Railway with the caption: 'We pledge allegiance to you with blood forever.' Blood drips from the words 'with blood'.[DD]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/travellers-syria-12-13-bashar-is-pledged-allegiance-in-dripping-blood.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Kurds on the Turkish borber, supporting their fellow Kurds battling for Kobane, Syria [October 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/kobane-kurds-on-turkish-side-oct-2014-_78284326_d9396def-f39b-40ec-bd44-0eaf58330353.jpg?w=300&h=168)

![The 'secret ceiling', an accidental discovery, that comes to represent the multi-coloured complexity of Syrian society [DD, 2013]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/bair-baroudi-may-2008-036.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Mar Yakoub Church and university, Nusaybin [DD, 2012]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/eastern-turkey-july-2013-123.jpg?w=225&h=300)

![The defunct border crossing from Nusaybin to Qamishli [DD, 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/eastern-turkey-july-2013-124.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Roman columns of Nisibis in the no-man's land between Nusaybin (Turkey) and Qamishli (Syria) [DD, 2013]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/eastern-turkey-july-2013-125.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Graves in the village of Anitli (Haho) [DD, May 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/midyat-8.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Syriac stone mansion in Midyat [DD, May 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/midyat-25.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Gabriel in his single room [DD, 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/midyat-29.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![The Syriac refugee camp on a hill outside Midyat [DD, May 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/midyat-26.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Midyat boutique hotel (Shmayaa) converted from a Syriac mansion [DD, May 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/midyat-7.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Father Joaqim, Syriac monk at Mor Awgen, near Nusaybin [DD, May 2014]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/midyat-12.jpg?w=300&h=225)