Raqqa, City of Contrasts

Today’s reality in Raqqa, claimed since 2014 as the capital of Islamic State, is hard to reconcile with its illustrious past as a leading city of the Islamic Golden Age.

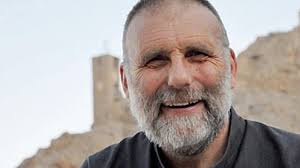

But Matthew Heineman’s powerful new film ‘City of Ghosts’, difficult to watch at times, does not concern itself with history. Its focus is the here and now, the story of the activist group Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently (RBSS), whose members are risking their lives to send the outside world painful footage from inside Raqqa, in their mission to counter ISIS propaganda. The documentary – in Arabic, with subtitles – follows four of the group’s leading members over the course of a year, starting from late 2015, and includes material recorded covertly in the city by RBSS and other footage from the Syrian revolution.

Nothing in Syria is straightforward and there are cruel ironies. The bird’s eye view given by aerial drone footage in the film’s early shots of Raqqa’s desolate flat landscape with its sprawling mess of modern buildings, is the same bird’s eye view the US-led coalition pilots will be getting from their cockpits as they bomb “a forgotten city in Syria” as Aziz, the main RBSS spokesman, calls his hometown.

“A few thousand extremists,” he laments, “are deemed justification to blow up civilians.” But he was talking back in 2016, not about the massive aerial bombardment campaign currently being waged on Raqqa by the government of the same country that has just given his activist group a top press freedom award, but about the handful of token airstrikes the Assad regime and its Russian ally had seen fit to conduct against the ISIS capital up to that point.

Over the coming months it is sadly inevitable that Raqqa’s civilians will be slaughtered all too loudly, as they get caught in the crossfire between ISIS mines and the majority-Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) seeking to ‘liberate’ them. The UN estimates that up to 50,000 of Raqqa’s original 300,000 inhabitants remain trapped inside the city as human shields, prevented by ISIS from leaving.

The famous Caliph Haroun al-Rashid, immortalised in the tales of A Thousand and One Nights, moved his capital in 796 from Baghdad to Raqqa on the banks of the mighty Euphrates River.

He built five hectares of palace complexes to symbolise his dominance of the region, from which his recreational summer palace Qasr al-Banat (Palace of the Maidens) and a colossal courtyard mosque with a 25m tower are all that remain today.

The Syrian astronomer Al-Battani (858-929), who calculated the 365-day length of the solar year to an accuracy of within two minutes and who is quoted as a major source by Copernicus over 600 years later, lived and worked in Raqqa.

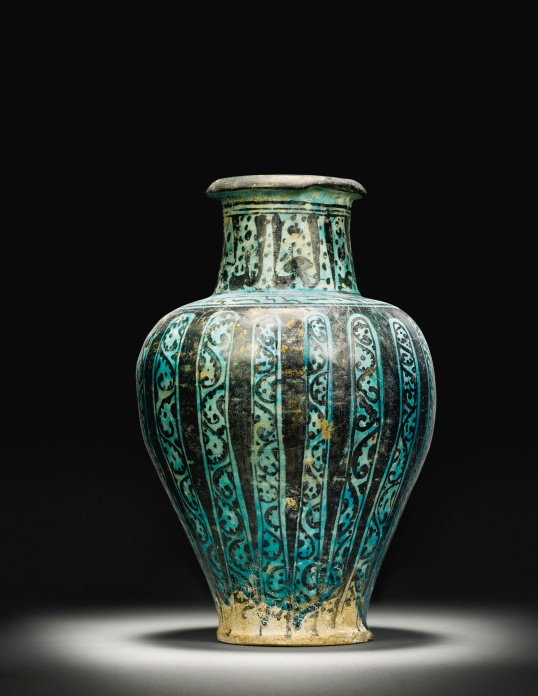

But while future generations will forever associate Raqqa with savagery and Islamist terrorism, the University of Nottingham’s excavations of the 1990s focussed almost exclusively on another of Raqqa’s claims to fame – its 2km-long industrial complex where, from the 8th – 12th centuries, the city manufactured glass and pottery, becoming the Islamic world’s most important glass-making centre.

The well-preserved glass furnaces produced green, brown, blue and purple glass on a commercial scale, made from quartz pebbles of the nearby Euphrates river-bed, combined with the ashes of plants that grow in the surrounding semi-desert environment. The skilled artisans were both Christian and Muslim, buried side by side in an area close to the kiln sites.

“Death is death, as we say in Raqqa” declares Aziz, claiming he has gone beyond fear in his fight against the jihadists. Yet it is clear, as the film follows its four main members of RBSS, that their constant battle to report ISIS atrocities has taken its toll on all of them, as they chain-smoke to settle their nerves and steady their shakes. The opening scenes, juxtaposing the high glitz of the New York awards ceremony with horrific shots of decapitated bodies in Raqqa, capture this well, exposing the gulf between the two worlds. A female US photographer tries to shoot photos of Hamoud, the RBSS photographer, urging him to smile for the camera: “You’re so serious, my friend!” she exclaims.

As the film moves back to Syria, it charts the heady days of the 2011 Revolution with its singing and peaceful demonstrations. “After forty years of Assad, we started to scream for freedom,” Aziz recalls, and the footage moves to Dera’a where “the deaths of fifteen children were the spark that ignited revolution”. He explains how he had no political background before then, and how his father, well-aware what would happen, warns him to stay away from journalism.

The film’s main focus throughout is the danger to the men as activists, a shared danger which deepens their bonds of friendship. As ISIS seeks to silence them, and as their colleagues and family members start to be assassinated, they decide to leave for Turkey’s Gaziantep, assuming it will be safe to continue their work from there. But ISIS is not so easily deterred and their co-founder and mentor Naji Jerf is shot in broad daylight on the city’s streets. The intimate scenes shot at his funeral are among the most moving in the entire film.

Some of the activists, including Aziz, are then granted expedited visas, immediate refugee status and free housing by the German government. Only Muhammad, a maths teacher, is married. His wife Rose is the sole female character to appear, and the film now shows footage of them all enjoying snowball fights in Berlin juxtaposed with surreal videos from Raqqa of casual street executions carried out by young ISIS recruits, their victims’ heads impaled on public railings. Mass destruction of satellite dishes is secretly filmed as ISIS cracks down on their activities, determined to cut them off from the world. Safely in Germany, they all suffer from survivors’ guilt. Hamoud, a self-described introvert, watches the video of his father’s assassination, posted online by ISIS, to “give me strength.” Meanwhile the friends experience the harsh reality of a Pegida anti-immigrant rally with heavily tattooed Germans chanting “One-way ticket to Turkey! Deport them!” Aziz is offered German police protection, from ISIS and from Pegida, but refuses it, feeling he cannot accept a protection that his friends lack.

A clear sense is given of how ISIS’s own films and propaganda material has become more professional through recruitment of media specialists, using Hollywood-style special effects to boost membership, making the ISIS lifestyle seem like a glorified video game. “Why play it online when you can play it for real?” reflects Aziz.

What the film does not explain is why ISIS chose Raqqa in the first place. They borrowed the black banner of the Abbasids, but their choice was much shrewder than their awareness of the city’s former glory. The last fifty years of Assad rule left Raqqa’s population neglected and exploited. Its poor and disadvantaged population, ripe with resentment and hatred of the regime, made it fertile ISIS recruiting ground. It is the only place in all of Syria where I have had stones thrown at me as a westerner. The takeover by a handful of extremists of an insignificant provincial backwater was considered unimportant by Assad, so his forces made no attempt to displace the ISIS fighters who first appeared in the city in early 2013. It was a bad miscalculation. The regime did not understand that Raqqa’s strategic location on the Euphrates,

downstream from Syria’s largest reservoir Lake Assad, and the main hydro-electric dam at Tabqa, together with its proximity to the country’s oil and gas fields, would give the pretender caliphate a disproportionate stranglehold on Syria’s infrastructure from the start. This part of Syria, well-watered, fertile, cotton and wheat-rich, should be the wealthiest in the country, but Bashar al-Assad’s regime, unlike his father’s, has always been urban-focussed, treating the assets of the provinces like possessions to be milked as if they belonged to his personal farm.

The film ends with a warning. In his speech to the assembled New York glitterati, Aziz explains that the conditions and structural problems in Syrian society which enabled the rise of ISIS are still there. Even if their territory is lost, he reads in halting English from his script, their ideology will continue to find supporters among the brutalised and unemployed youth with nothing to lose. When Hamoud becomes a father in Germany (his wife is invisible) the responsibility changes everything for him: “I don’t want my child to struggle like me without a father.” He names his new-born son after his assassinated father, and footage moves from the German hospital where the naked baby gurgles and kicks, to a chilling scene showing Raqqa’s Caliphate Cubs chanting death slogans. A child barely older than a toddler uses a huge knife to saw the head off a startlingly white teddy-bear, then beams, holding up the head triumphantly for the camera and squealing Allahu Akbar on cue.

To recover from such barbarity I recommend a visit to the glass displays of London’s V&A Museum. Gaze at the exquisitely delicate Raqqa perfume bottles, and ponder the fall of such a city, which in happier times centuries ago was known for its beautiful artisanal creations, its earth-changing scientific inventions, its multicultural environment and its magnificent summer palaces – all fostered by an enlightened, outward-looking Islamic state.

Exquisite glass perfume bottles made in Raqqa, displayed in London’s V&A Museum (DD)

Published in The TLS on 26 July 2017:

https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/private/raqqa-is-being-slaughtered-silently-rbss/

Mount Qassioun, seen across the rooftops of Damascus

Mount Qassioun, seen across the rooftops of Damascus A blacksmith made a new metal door to cover the smashed antique one.

A blacksmith made a new metal door to cover the smashed antique one. Checkpoints and road blocks, such as this one in Yusuf al-Azma Square, are a common sight

Checkpoints and road blocks, such as this one in Yusuf al-Azma Square, are a common sight

![All that remains of St Simeon Stylites' pillar in St Simeon's Basilica west of Aleppo, thanks not to the current fighting, but to Christian pilgrims harvesting 'souvenirs' across the centuries [DD]](https://dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/damascus-trip-july-2010-067.jpg?w=225&h=300)