The Turkey/Syria Earthquake strikes at the birthplace of civilization

The sheer scale of the disastrous series of earthquakes in southeast Turkey and northwest Syria is hard to absorb, especially in a region already blighted by a decade of war, displacement, drought and disease. As if that were not sufficient punishment, the cruel weather has added another layer of suffering with its comfortless blanket of snow, making rescue efforts even tougher, whilst leaving thousands of shell-shocked souls to freeze in the open, homeless.

For many outside the region, it may seem a faraway tragedy that has no direct bearing on their own lives. But as someone who has visited the area repeatedly over several decades, I feel that, beyond the humanitarian crisis unfolding day by day, there is a bigger picture that needs to be explained, to help grasp how connected we all are by oft-forgotten historical and cultural ties.

Historical and Cultural Context

The discovery in the 1990s of the world’s oldest temples, a series of mysterious circular structures on the summit of Göbekli Tepe (‘Pot-bellied Hill’ in Turkish), turned all previous perceptions of man’s early history on their head. Overlooking the once lush grasslands of the Fertile Crescent, northeast of Urfa, they were built by nomadic hunter-gatherers some 12,000 years ago, pre-dating Stonehenge by 6,000 years, and the world’s earliest city at Çatalhöyük, also in eastern Turkey, by a full 3,000 years.

Similar groupings of circular temples have been identified in northern Syria, collectively proving that man’s first construction efforts, were devoted, not to building settlements, but to the worship of deities connected with the sun, the moon and the circular seasonal cycles on which he depended. The temples were first unearthed in 1994 by German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, who tragically died before seeing UNESCO inscribe them on its World Heritage List in 2018.

World heritage sites

As recently as 2021, UNESCO added the late Hittite site of Aslantepe (‘Lion Hill’) near Malatya and the Euphrates, in recognition of its significance in illustrating how a State society first emerged in the Near East, along with a sophisticated bureaucratic system that predated writing. Among the finds were the world’s earliest known swords, evidence of the first forms of organised combat used by the new elite to maintain their political power.

Towering above the Tigris, UNESCO’s other World Heritage Site (2015) that lies within the earthquake zone is the brooding city of Diyarbakir, whose mood seems reflected in its massive black basalt walls. It too is part of the ancient Fertile Crescent, an important regional centre commanding the surrounding fertile plains throughout Hellenistic, Roman, Sassanid Persian, Byzantine, Islamic and Ottoman times. Its elegant ‘Ten-Eyed’ bridge, built by the Seljuks in 1065, still spans the river below.

Further testimony to the onetime prosperity of the region is the site of Zeugma on the Euphrates, famous for its collection of superb mosaics, among the finest in the world. Once a thriving frontier town on the eastern edges of the Roman Empire, where 5,000 troops were garrisoned to defend against the Persians in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, it was also known as Belkıs, a reference to the Queen of Sheba and her legendary wealth. Rescued, along with many other ancient sites, from the flooding caused by the modern Birecik Dam on the Euphrates, the spectacular mosaics graced the floors of rich villas, but today are housed a new purpose-built museum in nearby Gaziantep, epicentre of the first 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck overnight on 5 February.

Those who know Aleppo will find in Gaziantep many echoes of that more famous Syrian city. Not for nothing did so many Syrian refugees fleeing war in their own country take refuge in Gaziantep as their city of choice. In the days before the artificial borders imposed by Britain and France after World War One, the two cities were closely linked. Easily the most sophisticated city in southeast Turkey, Gaziantep, long hailed as the pistachio capital of the world, boasts around its prominent Seljuk citadel an old quarter, much of which was built by the Ottoman Governor of Aleppo. Like Aleppo, it has a mixed Muslim/Christian population, with its Christian population in Ottoman times likewise much larger than today. Their churches and mansions are still scattered about the old Christian quarter, often now converted to musical venues or boutique hotels. The citadel itself has suffered damage in the earthquake, so the historic quarter of which it forms the heart must also have been affected. Like Aleppo’s historic centre, it was the subject of extensive restoration projects, and experienced boom-level growth in recent times, its citizens deeply proud of their shared heritage and identity.

Border ironies

Earthquakes do not recognise political boundaries, and just as Gaziantep was part of the Ottoman Province of Syria till 1922, so Aleppo too, less than 200km to the south, has suffered damage, both to its iconic citadel mound and to its surrounding historic areas. Friends have told me of their homes, newly restored from the war, damaged once again, by force majeure, as if accursed. Aleppo’s Great Umayyad Mosque, located at the foot of the citadel, has been undergoing restoration funded by Putin’s ally, the Russian politician Ramzan Kadyrov, President of Chechnya. The mosque’s unique 1,000 year-old Seljuk minaret miraculously survived many earlier earthquakes, only to collapse in cross-fire in 2013. Its rebuilding is a dauntingly complex jigsaw that is in progress, 60% complete, which has somehow survived this quake.

In more border ironies, the Province of Hatay in southeast Turkey belonged to Syria till 1939. Known before then as the Sanjak of Alexandretta, it was incorporated into Syria under the French Mandate in 1918 at the Ottoman Empire’s demise, but the French then gave it to Turkey in anticipation of a new war against Germany, a bribe to buy Turkish neutrality. Syrians have never accepted the transfer and most Syrian maps still show it as part of Syria.

Now eclipsed by the mosaics at Zeugma, Hatay boasts its own, much older mosaic museum in its capital city of Antakya, ancient Antioch, also hit by the earthquake. Built by the French, it was considered in its day second in the world only to the Bardo Museum in Tunis, displaying, in scenes like Narcissus and Echo and the Drunken Dionysus, the licentious lifestyle of banqueting and dancing against which the early Christians here preached. St Peter’s Rock Church cut into the cliffs behind the city was founded in 47CE by Peter, Paul and Barnabas as the first church after Jerusalem. Matthew is said to have written his Gospel in Antioch. Even before the arrival of Christianity, the city was very mixed, with Greek, Hebrew, Persian and Latin all spoken in its streets. ‘If your aim in travelling is to get acquainted with different cultures and lifestyles, it is enough to visit Antioch’, wrote Roman historian Libanius. ‘There is no other place in the world that has so many cultures in one place.’

Cycles of history

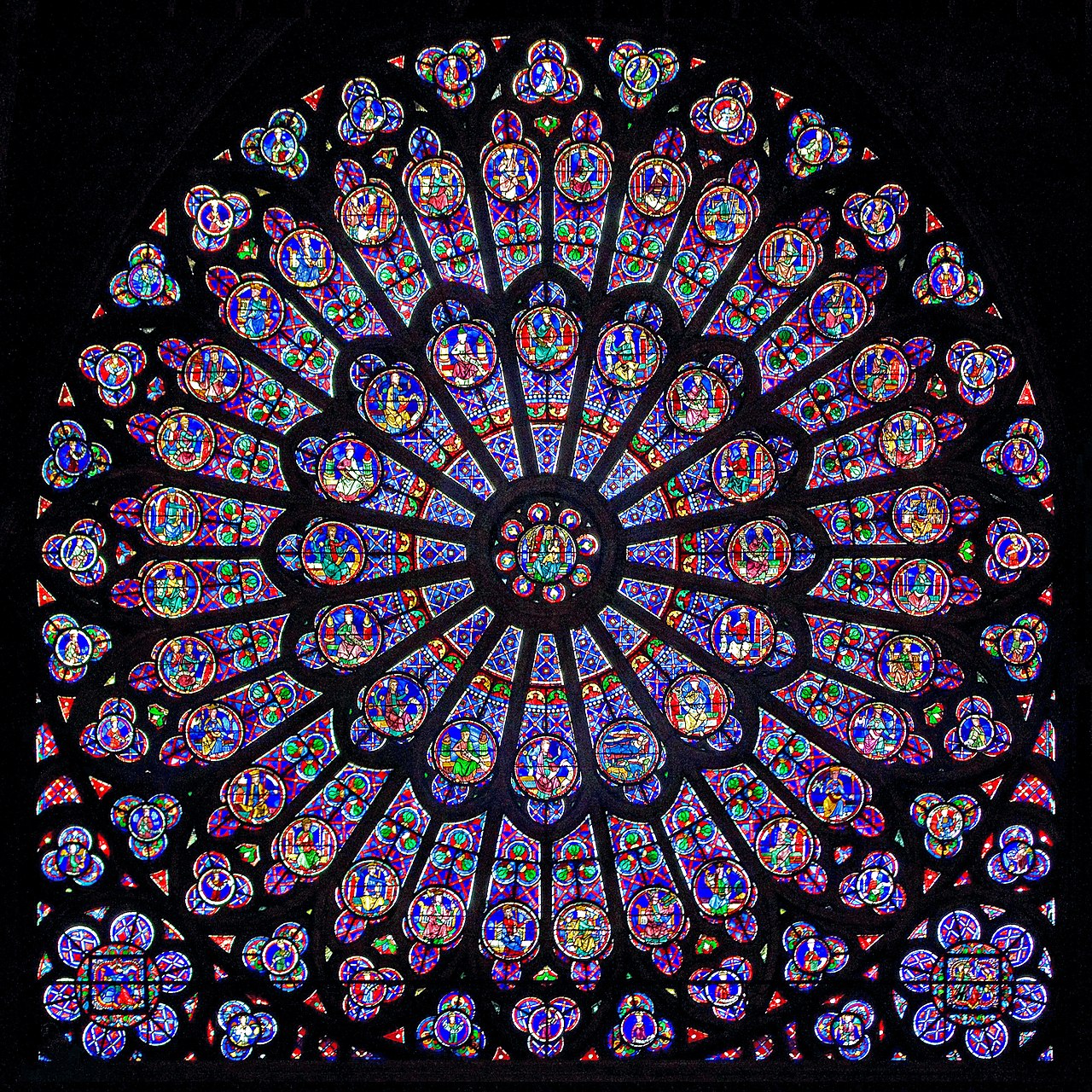

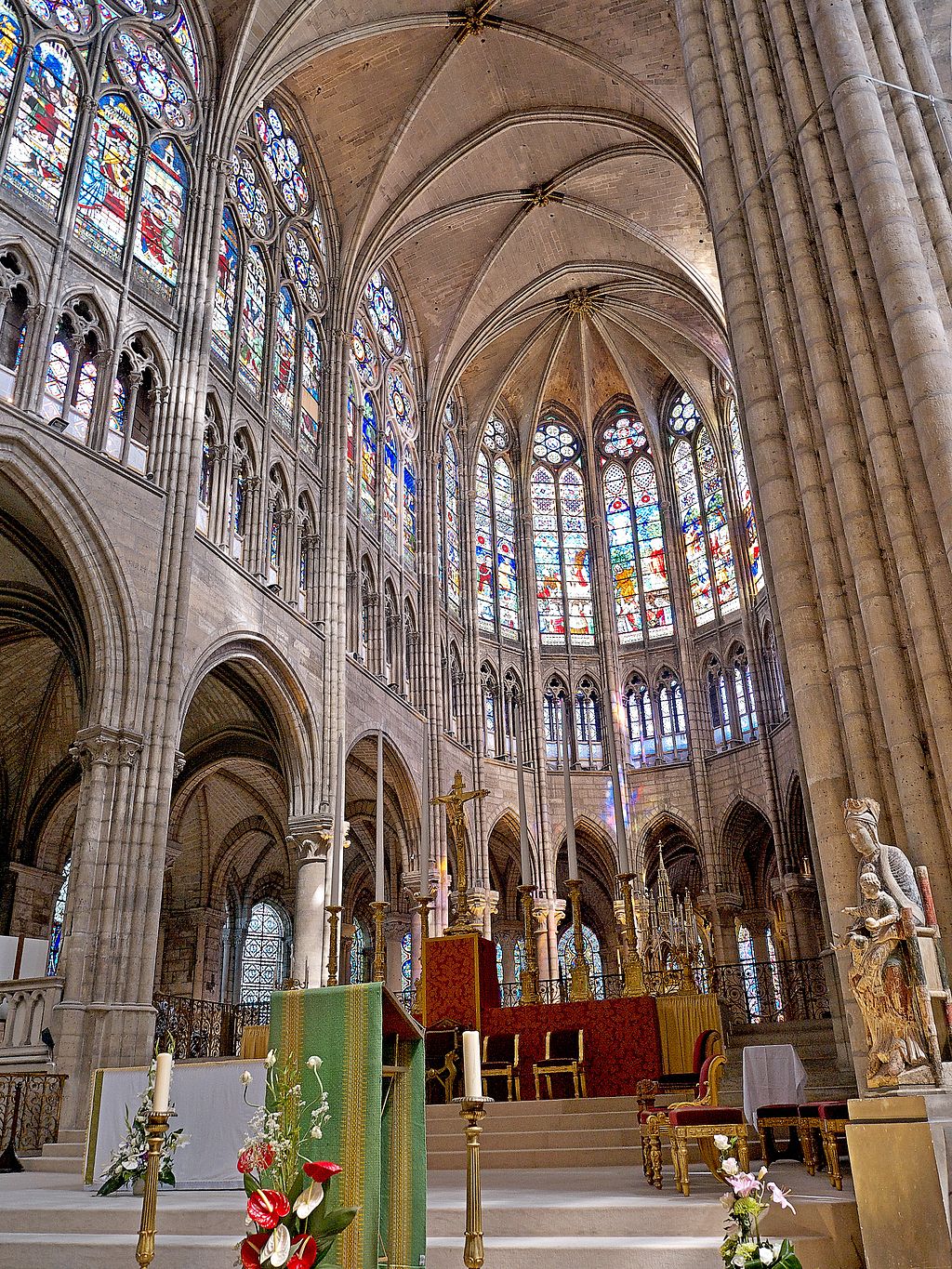

Today the population remains very mixed, with large communities – both Muslim and Christian – blended together. Among the early churches in Antioch was the octagonal Domus Aurea (Golden House), a magnificent structure thought to have been Constantine the Great’s palace chapel, built in 327CE. Destroyed by fires and earthquakes in 588, its exact location is lost to us today, but it is known through the description of contemporaries to have served as the prototype for the octagonal Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, from where the Emperor Charlemagne took his inspiration for his own palace chapel at Aachen, Germany.

Parts of the Crusader castle of Marqab, built from black basalt to dominate the Mediterranean coastal plain, are also damaged from the earthquake, with collapsed towers. Second in power only to the mighty Krak des Chevaliers, its cellars were stocked with enough provisions to last a thousand men for a five-year siege. Originally an Arab stronghold fortified in 1062, it was captured by the Byzantines in 1104, then sold to the Knights Hospitaller. It fell following a brief siege to the Mamluk army of Sultan Qalaoun in 1285, who whitewashed and thus preserved the frescoes in the chapel. One depicts a striking vision of Hell in which a huge bishop is sitting naked in a fire, with two devils tending the flames, along with two monster-headed figures flying overhead.

Such cycles of history, filled with so many seismic twists and turns like earthquakes, wars and invasions, have all played their part in the ever-shifting balances of power in this region of great strategic significance. When looking at the horrors that are unfolding in southeast Turkey and northwest Syria today, it is impossible to predict how the current disaster will shape the future of this most volatile of regions.

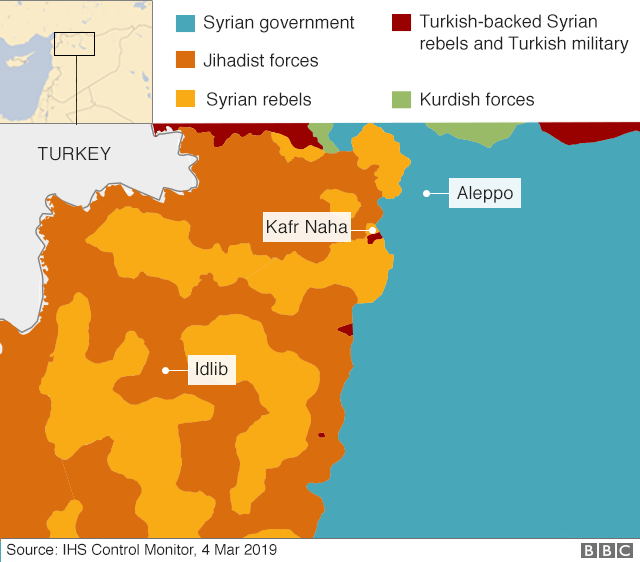

The complex political landscape at play in both countries is likely, without huge international support, to hamper progress towards the imperative delivery of aid, while fledgling efforts that were underway for restoration of cultural heritage sites, especially in the blighted and fractured territory of Syria, will inevitably be pushed even further down the agenda.

Past parallels show us that rival powers are likely to continue to vie for control of this once Fertile Crescent, where the tectonic plates of so many past civilisations have struggled for survival, in ways that have shaped us all.

This piece first appeared in Middle East Eye on 9 February 2023:

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/turkey-syria-earthquake-birthplace-civilisation-strike

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA 5th century stonework carving [copyright Diana Darke]](https://dianadarke.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-048.jpg?w=265&resize=265%2C199#038;h=199)

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA The apse at Qalb Lozeh, 5th century [copyright Diana Darke]](https://dianadarke.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-061.jpg?w=265&resize=265%2C199#038;h=199)

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA What remained of the pillar of St Simeon Stylites, at the centre of the four basilicas in July 2010. [copyright, Diana Darke]](https://dianadarke.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-067-st-simeons-pillar.jpg?w=191&resize=191%2C254#038;h=254)

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA The chevet at St Simeon's Basilica, completed by 490. [copyright Diana Darke]](https://dianadarke.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-073-st-simeon.jpg?w=339&resize=339%2C254#038;h=254)

![20190426120125_01 Church of Bissos Ruweiha The Church of Bissos, Ruweiha, 6th century [copyright Diana Darke, February 2005]](https://dianadarke.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/20190426120125_01-church-of-bissos-ruweiha.jpg?w=265&resize=265%2C177#038;h=177)