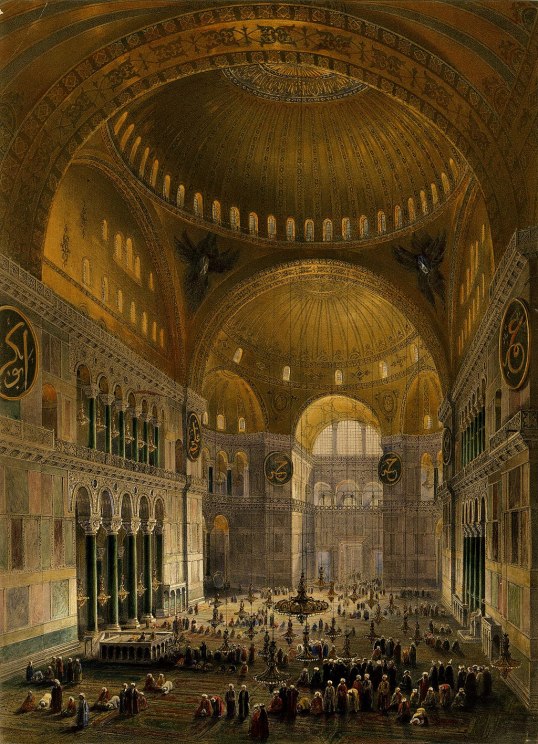

Hagia Sophia’s conversion from a museum into a mosque has seen thousands and thousands of words committed to the page across the globe.

Most of it recycles the same information – that the great church was built in the sixth century under the Byzantine emperor Justinian, that it was converted to a mosque when Mehmed the Conqueror captured Constantinople in 1453 and that Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, founder of modern Turkey, repurposed it as a museum in 1934.

All this is true but misses so much of the flavour and historical context of this hugely important building.

The tone of much western coverage is pained, as if the Hagia Sophia is somehow part of a European Christian cultural heritage now wrenched away into the dark folds of Islam by a Turkish president with neo-Ottoman delusions.

There can be no doubt that President Erdogan does indeed have his own agenda for converting Hagia Sophia into a mosque, and his timing is clearly political. It heightens his popularity with his core Islamic supporters at a time when the Coronavirus pandemic is running amok with Turkey’s struggling economy, and provides a welcome distraction. He makes no apology for his actions – and an Optimar poll show 60% of Turks support the move.

The important thing to understand is that the Hagia Sophia – like so many religious buildings – has its own highly political backstory. As ever the architecture reflects the politics in visible form and the current events are but the latest in a long line of twists and turns.

Ethnically diverse

The first church on the site was built in 360, but there is no evidence that it had Christian mosaics on the walls of the type found from the fifth and sixth century onwards. Walls instead were covered with marble revetments, plaster, and painted and gilded stucco in decorative patterns. Constantine denuded virtually every city in the empire of its pagan statuary to adorn Constantinople, his new Rome, just as Justinian scoured the empire for precious marble two centuries later, like the eight green columns from the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, to build Hagia Sophia.

When the Western Roman Empire and Rome itself collapsed in 476, Constantinople became the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, and the influences upon it were wide and varied, including from the Roman Latin culture, the Egyptian Copts, the Thracians, Macedonians, Illyrians, Bythinians, Carians, Phrygians, Armenians, Lydians, Galatians, Paphlagonians, Lycians, Syrians, Cilicians, Misians, Cappadocians, Persians, and later the Arab Muslims.

Many Europeans call the Byzantine Empire ‘Greek’, when in practice it was very ethnically diverse. Greeks composed a relatively small portion of this multi-ethnic empire, and most Byzantine emperors were not ethnic Greeks.

Justinian was obliged to build the current Hagia Sophia after it was damaged beyond repair by angry crowds protesting his high taxes. According to art historian John Lowden, Justinian was ‘a person of vision and extraordinary energy, both intensely pious and utterly ruthless … his military ambitions matched by his grandiose building programme.’

Reconstructing Hagia Sophia

To re-establish control as quickly as possible, he commissioned two famous architects in 532, both from western Asia Minor, to complete the project with a huge workforce over an intense five-year period. Both ignored numerous stylistic quotations and detailed instructions from the emperor to come up with their own unique creation, universally recognised as the highpoint of Byzantine architecture and admired round the world for the stunning achievement of the central dome.

A very different image is conveyed by the western European Latin manuscript now held in the Vatican Library, in which an enormous Justinian, many times bigger than the Hagia Sophia itself, is seen directing a small, rather nervous-looking mason who is balancing on a ladder.

The inspiration for Hagia Sophia was never Hadrian’s Pantheon, but earlier Eastern traditions. St Simeon’s Basilica, in Syria west of Aleppo, completed in 490, was the largest and most important religious establishment in the world for fifty years before the construction of Hagia Sophia.

It also inspired the UNESCO World Heritage Site basilicas of Ravenna, briefly capital of the Western Roman Empire, where all the bishops up till 425 were Syrian and whose patron saint Apollinaris was a native of Antioch.

Famed across Europe as a site of pilgrimage, the Santiago de Compostela of its day, St Simeon’s could hold 10,000 worshippers, more than Notre-Dame de Paris or the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny.

The heavenly temple

Hagia Sophia was the largest cathedral in the world for over a thousand years, a major influence on and inspiration for future religious architecture, both Christian and Muslim. A series of earthquakes caused it to fall in 558, just twenty years after it was completed, by which time Justinian was seventy-six and both architects had died.

Sections of this second dome, completed in 562, collapsed again in 989 and in 1346, but were restored and repaired without material change. It was a remarkable achievement, openly praised by later Ottoman historians—following the typical Byzantine tradition, they used language implying that the architect must have worked in direct union with God, with descriptions of a guardian angel watching over the church.

Even before the Ottoman conquest of the city, Islamic tradition had identified Hagia Sophia as the heavenly temple that the Prophet Muhammad had seen on his nocturnal journey to heaven from Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, which was understood to predestine the church’s conversion to a mosque.

In 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, Hagia Sophia suffered the greatest damage in its long history, looted and sacked, along with the whole of Constantinople, thereby consummating a major schism between the Latin and Greek churches—Roman Catholics against Greek Orthodox Christians.

For three days they murdered, raped, looted and destroyed.

The Fourth Crusade

The defeat of Byzantium, already in a state of decline, accelerated political degeneration so that the Byzantines eventually became an easy prey to the Turks. The Fourth Crusade and the crusading movement generally thus resulted, ultimately, in the victory of Islam, a result which was of course the exact opposite of its original intention.

Pope Innocent III, who had unintentionally launched the ill-fated expedition, rebuked them:

“How, indeed, will the church of the Greeks, no matter how severely she is beset with afflictions and persecutions, return into ecclesiastical union and devotion to the Apostolic See, when she has seen in the Latins only an example of perdition and the works of darkness, so that she now, and with reason, detests the Latins more than dogs? As for those who were supposed to be seeking the ends of Jesus Christ, not their own ends, who made their swords, which they were supposed to use against the pagans, drip with Christian blood, they have spared neither religion, nor age, nor sex. They have committed incest, adultery, and fornication before the eyes of men. They have exposed both matrons and virgins, even those dedicated to God, to the sordid lusts of boys. ..They violated the holy places and have carried off crosses and relics.”

The pope’s outrage however did not prevent him accepting the stolen jewels, gold, money and other valuables, and the Church was much enriched as a result. A great deal of this wealth was in turn repurposed into huge building projects throughout Europe— much of it decorates St Mark’s Basilica in Venice and some of it certainly would have helped to finance Europe’s Gothic cathedrals.

Remorse was expressed 800 years later by Pope John Paul II for the events of the Fourth Crusade. Writing to the archbishop of Athens in 2001, he said:

“It is tragic that the assailants, who set out to secure free access for Christians to the Holy Land, turned against their brothers in the faith. The fact that they were Latin Christians fills Catholics with deep regret.”

Shared symbolism

When Mehmet the Conqueror took Constantinople in 1453, he permitted his armies three days of looting, as was the custom, but then called a halt.

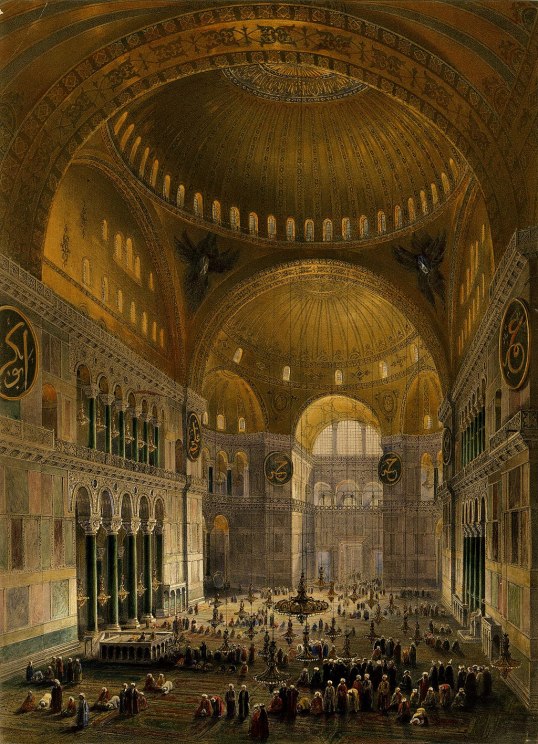

Most churches were allowed to continue functioning, but the Hagia Sophia was adopted as a mosque. Mehmet erected a minaret and subsequent sultans erected three more, so there is now one at each corner, but the interior remains largely as it ever was.

There is much shared symbolism between Christianity and Islam in the meaning of the dome as the physical representation of heaven and the afterlife, but the flavour of Hagia Sophia as a building was always different to the sacred buildings of Rome like the pagan Pantheon and Michelangelo’s St Peter’s.

Its design was rooted in Eastern traditions, where Persian mausoleums had a circular dome resting on a square drum. The transition between the circle and the square resulted in an octagon, which came to represent, both in Christianity and Islam, the resurrection and the journey between earth and heaven, which is why so many tombs are octagonal in both religions.

As well as shared concepts, Christians and Muslims in the eastern Mediterranean enjoyed a common heritage of building materials, techniques and tools passed on from the Graeco-Roman, Persian and even earlier Etruscan worlds.

They also shared workers, builders and craftsmen, who moved around according to demand, following the next or the most profitable commission from a wealthy patron, no matter what his religion. Byzantine mosaicists, for example, were frequently employed to decorate Islamic mosques, such as the Dome of the Rock, the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, and the Cordoba Mezquita.

In 1573 the great Ottoman architect Sinan was commissioned to strengthen Hagia Sophia, which was again starting to show signs of possible collapse. Extra buttressing was added to the outside to ensure its resistance to earthquakes.

In total, twenty-four buttresses have been added over the centuries to ensure its stability, making its external appearance quite different to how it would have looked originally.

In today’s world of intense economic pressures, a final mention should be made of the loss of revenue to the Turkish treasury through the conversion of Haghia Sophia to a mosque. Like the Blue Mosque next door, and like all mosques in Turkey (unlike many cathedrals and churches in Europe) entry will now be free to all.

The entrance fee to Hagia Sophia as a museum was expensive, c$15 per person. Maybe we should celebrate the fact that Muslims and non-Muslims alike can today make repeated visits to admire the blended architecture of Christianity and Islam on display for free in this unique building, standing on its promontory between East and West.

This article first appeared in Middle East Eye on 31 July 2020:

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/hagia-sophia-backstory-Islam-Christianity-shared-history