Syrian Secrets rising from the ashes of Notre-Dame

Notre-Dame roof and spire aflame on 15 April 2019, but structure intact. Photo from Wikipedia LeLaisserPasserA38.

Who would have thought that last year’s catastrophic fire at Notre-Dame de Paris would reveal so many secrets from its ash? A team of scientists has been gathered under the leadership of a military general to conduct deep background research into the fabric of the cathedral, hoping to understand how on earth the medieval masons and craftsmen made the building stand up. Nothing was written down, no plans were used. The study will take an estimated six years, helping to guide the restoration work.

The fire also sparked my own desire to study further. This time last year I wrote an article explaining the architectural backstory of the cathedral, how, like all medieval Gothic cathedrals, the origins of its twin towers flanking a monumental west entrance, its pointed arches, its rose windows, its ribbed vaulting can all be traced to the Middle East. Now, after extensive research, I have discovered many more connections, all of them unexpected. The full results will appear in my forthcoming book Stealing from the Saracens: How Islamic Architecture shaped Europe: https://www.hurstpublishers.com/book/stealing-from-the-saracens/

Meanwhile, here are just a few pointers, to give the flavour. Let’s start with the stained glass, thankfully still intact after the fire. Recent analyses of stained glass in the main cathedrals of England and France between 1200 and 1400 all show the same high plant ash composition typical of Syrian raw materials. High-grade Syrian plant ash soda, known as ‘the cinders of Syria’, was considered superior to the pre-Islamic Egyptian natron ash used by the Romans and the Byzantines in their glass manufacture, and all Venetian glass analysed from the 11th to the 16th centuries shows its consistent use, by law. Medieval Continental Europe imported the raw materials for all its glass since there was no known local source.

Coloured glass windows have been an integral and innovative element of Islamic architecture since the 7th century, starting with Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock which carried coloured glass in its many high windows. They were known as shamsiyyat (from Arabic for sun) and qamariyyaat (from Arabic for moon), showing how the solar and lunar imagery of windows continued into European religious architecture. The Templar knights adopted the Dome of the Rock as their chief Christian shrine after the First Crusade, mistaking it for the Temple of Solomon, an error which resulted in many churches being modelled on a Muslim shrine. Notre-Dame’s famous rose windows on its west and north facades date from 1225-50 and are designed for the light to radiate out from the centre, hence the so-called Rayonnant style.

Notre-Dame Rayonnant-style North Rose Window, c1250, photo from Wikipedia, by Zachi Evenor and Julie Anne Workman, Aug 2010.

Light was also at the core of Gothic cathedral design. Saint-Denis in north Paris was where the wealthy and powerful Abbot Suger first used Illuminationist thinking as the guiding principle in his new basilica. But who was Denis?

The martyr Denis, Bishop of Paris, holding his head after decapitation on Montmartre, Notre-Dame, Portal of the Virgin, photo from Wikipedia by Thesupermat, Sept 2011.

The Abbot and his contemporaries believed him to be a disciple of Paul, who later became confused with the first Bishop of Paris and patron saint of France, martyred on Montmartre. Centuries later, scholars realised that Denis’s influential work the Celestial Hierarchies, was in fact a hoax, written by a 5th century Syrian mystic monk calling himself Denis in order to get his philosophy noticed. As a result he is known in ecclesiastical circles as Pseudo-Denis, but his trick worked. Today the Basilica of Saint-Denis is universally acknowledged as the first true example of ‘Gothic’ with tall pointed arches enabling the lofty elegant choir. It was used thenceforth as the burial place of French kings.

Basilica of Saint Denis, the first, new, light-filled ‘Gothic’ choir, based on the philosophy of Denis, a 5th century Syrian mystic, photo from Wikipedia by Bordeled, July 2011.

The very symbol of French nationhood and French royalty is the fleur-de-lis. But where was that first seen as an emblem? On the plains of Syria the Crusaders copied the local sport of ‘jarid’, knightly jousting tournaments on horseback where the players attempted to dismount each other with a blunt javelin. Heraldry and the use of family or dynastic symbols was already in use under the Ayyubids and the fleur-de-lis first appeared in its true heraldic form, the three separate leaves tied together in the middle by a band, as the blazon of Nur al-Din ibn Zanki and on two of his monuments in Damascus. Later Mamluk helmets often had nasal guards terminating in a fleur-de-lis. The boy king of England, Henry VI, was crowned king of France aged ten inside Notre-Dame in 1431, against a backdrop of fleur-de-lis.

Coronation of the boy king Henry VI as king of France inside Notre-Dame, against a backdrop of fleur-de-lis, photo from Wikipedia public domain.

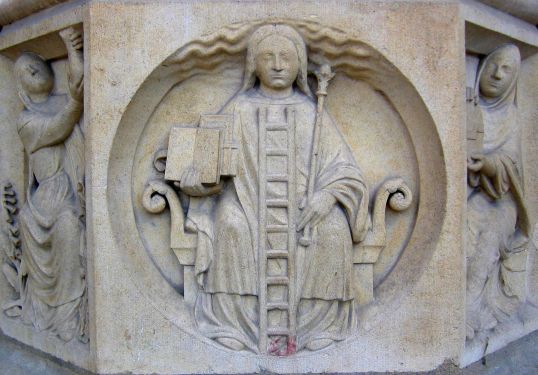

Notre-Dame’s central portal carries a stone-carved allegory of Alchemy, a statue of a woman holding books with a ladder and staff. The very word comes from the Arabic al-kimya’ and in medieval times the Middle East was widely acknowledged as the home of advanced experimental science. The use of plant ash in glass was itself a kind of alchemy, an experiment in which the addition of the alkaline (from qily another Arabic word) plant called ushnaan to the silica of the crushed pebbles of the Euphrates produced the world’s finest and most delicate glass, based at Raqqa, the centre of the Syrian glass industry from the 9th to the 14th century. The addition of further chemicals coloured the glass, cobalt for blue, copper oxide for turquoise, manganese for purple/pink and so on.

Notre-Dame Allegory of Alchemy on the central portal, photo from Wikipedia by Chosovi, April 2006.

But the ashes of ushnaan also had other properties. They had been used since biblical times as a cleaning agent (Aramaic shuana) where there was no access to water, both in personal hygiene and in clothes laundry. To this day it remains an essential natural ingredient in the Syrian soap industry, as the plant grows especially well south of Aleppo round the salt lake of Jaboul. This is what gives Aleppo soap such a wonderfully soft and silky feel on the skin. It even has the bubbles trapped inside just like the Syrian glass.

Stained glass c1180 from Canterbury Cathedral, showing the trapped bubbles from the plant ash. These bubbles also gave the glass extra strength, making it less liable to fracture. Photo by Diana Darke, taken 3 March 2020 in the V&A Museum, London

The team of scientists at Notre-Dame have made their own unlikely cleaning discovery – that the best way to remove the toxic yellow lead dust from the stained glass windows without danger to the colours is to use baby wipes from Monoprix. The commercial chemical wipes risked being too abrasive. Gentle Aleppo soap would no doubt be even better. How fitting it would be if the cathedral could be cleaned using the very same plant ash that is already inside its stained glass windows.

Syrian soap from Aleppo, with bubbles, made using Syrian plant ash known as ushnaan, famous for its natural cleansing properties, photo by Diana Darke, taken 31 March 2020

A version of this article first appeared in Middle East Eye on 14 April 2020:

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/syrian-secrets-notre-dame