Rebuilding Damascus

With its future in the balance, a cultural historian looks past the corruption, violence and trauma of recent decades to the almost lost history of collaboration and shared traditions between Muslims in Syria and Christians in Europe. By DIANA DARKE [as first published 10 January 2025 in The Tablet]

Buildings have stories to tell, in Syria none more perhaps than the magnificent Umayyad Mosque in the heart of the walled Old City of Damascus. It embodies the very soul of Syria, a sacred site where for over two millennia multiple civilisations and religions – Aramean, Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic – have coalesced yet also survived in their own unique form. No surprise, therefore, that the new de facto ruler of Syria, Ahmad al-Shar’a, leader of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, the Organisation for the Liberation of Syria (HTS), chose to head straight there to pray after entering the city on 8 December.

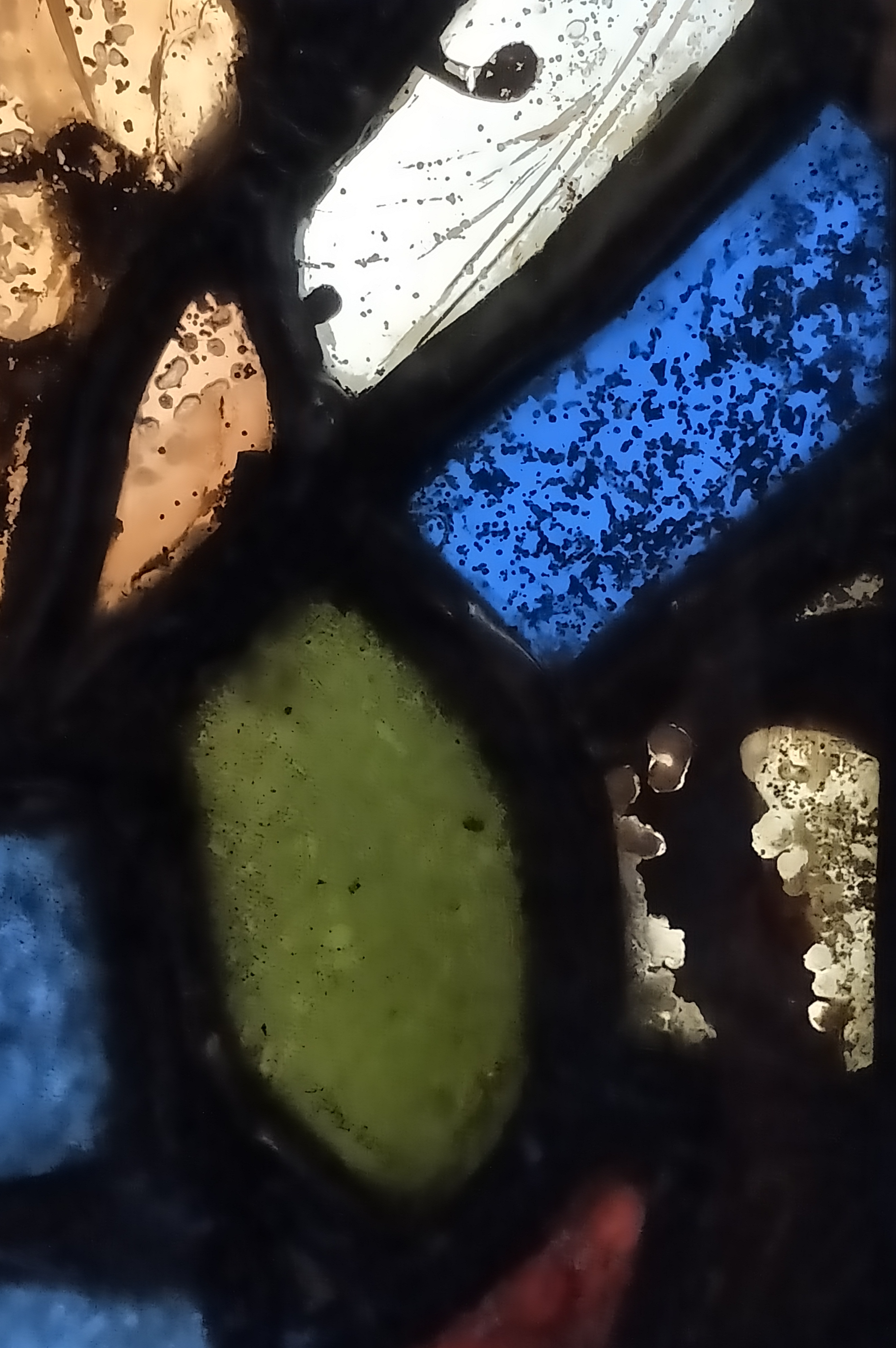

Syria has long been overwhelmingly Muslim but the Umayyad Mosque claims the heads of John the Baptist as well as Hussein, the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson. While still a cathedral, following the Muslim conquest of Damascus in 634, the building was shared by Christians and Muslims for close to a hundred years, as were the cathedrals of Homs and Hama. They were only converted to mosques once the Muslim population, small at first, gradually expanded. Top Byzantine Christian mosaicists then followed the brief of new Umayyad masters to cover the walls of the courtyard with breathtaking visions of the Islamic Paradise, timeless landscapes of fantasised trees, gardens, rivers and palaces in shimmering green and gold.

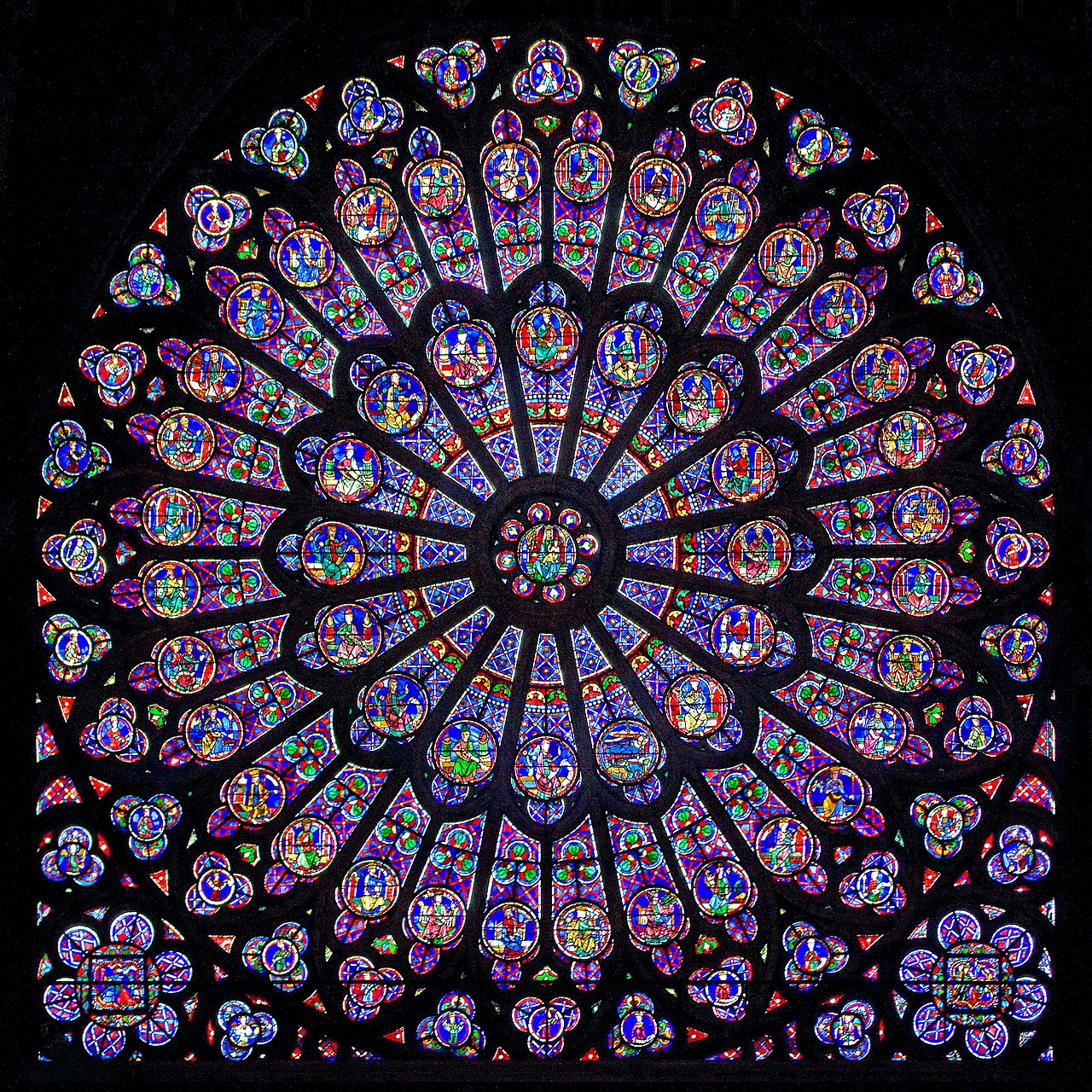

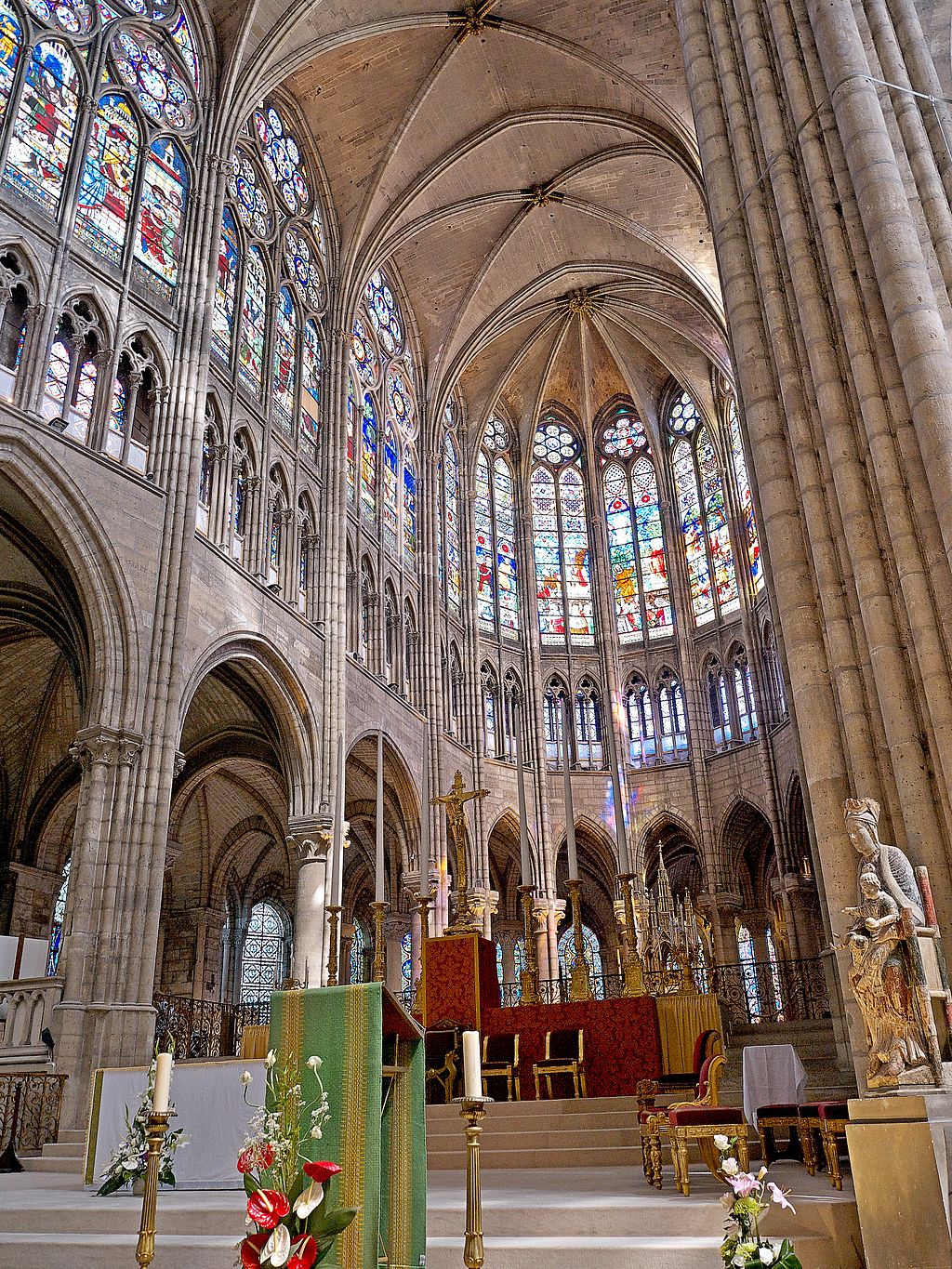

When rulers change, life for those uninvolved in the fighting tends to continue as before. The best architects and craftsmen are summoned to work on new prestige projects, irrespective of their religion, just as the most entrepreneurial businessmen find new opportunities. It was the same in Umayyad Spain when elite Muslim craftsmen were summoned by new Christian rulers during the Reconquista, to transfer their innovative engineering technologies like pointed arches and ribbed vaulting, as well as their decorative repertoires, to prestige abbeys and cathedrals. As late as 1492 the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella appointed a Muslim master builder to look after all royal buildings in Aragon, a position that then passed to his son.

I bought a semi-derelict Ottoman courtyard house in Old Damascus in 2005. Full of wonder that I, as a foreigner, was able to buy a chunk of a UNESCO World Heritage site, I embarked on a three-year restoration project, guided by a Syrian architect and a team of fifteen craftsmen, experiencing first-hand the labyrinthine corruption of government and legal systems. To learn more about the house itself, I re-entered the academic world to study Islamic art and architecture. Deciphering the decorative styles of the house gave me the essential foundation for my subsequent work, connecting the almost lost history of collaboration and shared traditions between Muslims in Syria and Christians in Europe, traditions that formed the springboard for the architectural styles we know in Europe as “Romanesque” and “Gothic”.

In the new Syria of 2025 a Christian wheeler-dealer who made a fortune during the war in the transportation business is now raking it in as a high-end hotelier. Among Aleppo’s traditional soap-making family businesses, trade is up by 80%. My lawyer, who throughout the war bemoaned the fact that most of his caseload was divorce work, is now kept busy by clients asking questions he cannot answer. Many, like me, had their houses stolen during the war by profiteers writing fabricated intelligence reports against them. By a miracle, despite being labelled a British terrorist with links to armed groups, I went back in 2014 and retook possession, evicting my previous lawyer, his mistress and baby, along with a fake general on a forged lease.

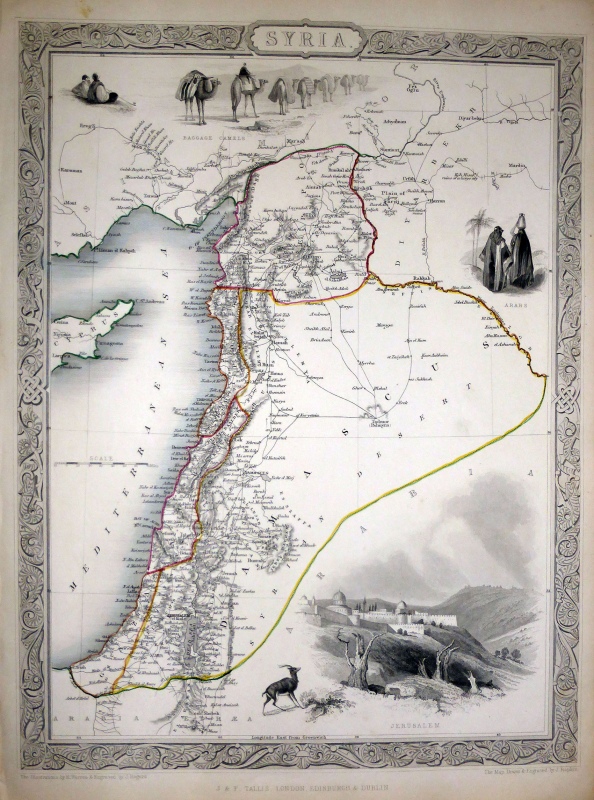

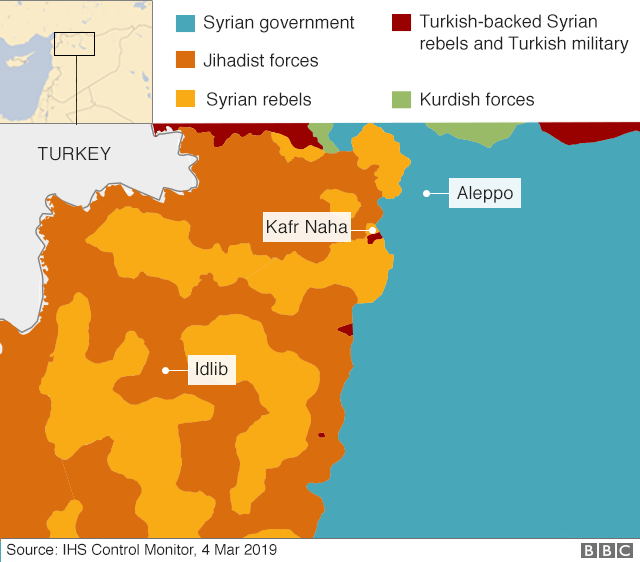

The interim government faces huge challenges. Disentangling the different currencies, legal and education systems that operate in the different regions of Syria will take a long time. Add to that the complication of how to monitor the movements of returning refugees, as well as compiling a new electoral roll, and the three-year period Al-Shar’a suggested last week will be needed to draft a new constitution – four years for proper elections – in a unified Syria, becomes an ambitious target.

Al-Shar’a has promised to make Syria inclusive for all, including women. The country’s central bank has just appointed its first-ever female governor. Many commentators outside the country gnash their teeth, convinced that HTS, a Sunni Islamist group once aligned with Islamic State and al-Qaeda, remains a jihadi extremist outfit similar to the Taliban. Yet at least so far, its leaders appear ready, as are the majority of Syrians inside the country, to take Syria on a new trajectory, and seem prepared to engage pragmatically with the “international community” that failed it so badly, some elements of which even went so far as to rehabilitate Assad as if he were a fact of life, never understanding how hollowed-out his regime was, how unrepresentative of the overwhelming majority of Syrian people.

Syrian friends forced into exile during the war (along with nearly a third of the Syrian population) are scattered across Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Germany, Norway and Canada. From a range of professions – architect, lawyer, hotelier, tour guide, environmentalist – not one of them was able to continue their former work in their host countries. All struggled to make new lives for themselves and they feel they have lost thirteen years of their life. Even harder to bear is how in recent years refugees from Syria have been made to feel increasingly unwelcome, the mood turning against them in their host countries as right-wing populism has risen to heights where it is destabilising Europe as well as Syria’s neighbours. Most now plan to return, to rebuild their lives and their country, bringing with them new expertise and knowledge. After Germany’s 6000-plus Syrian doctors have left, they will be missed by its aging population, their worth only recognised once it is too late. Friends who stayed also feel the last thirteen years have been wasted, their country devastated by aerial bombardment from the Assad regime and Russia, sanctioned and isolated from the outside world.

Nothing screams “CHANGE” to me more loudly than the sudden arrival since 8 December of the world’s media, banned since 2011. During the 54 years of the Assad dynasty’s rule – 30 years under Hafez from 1970 till his death from leukemia in 2000 and 24 years under his second son Bashar – it was never easy for journalists to get visas into Syria. Control of the narrative was always an essential part of the Assad grip on power.

“Come in and report without restriction” was the message from al-Shar’a. In a country with so many secrets to uncover it is a journalist’s dream come true. Heartwarming scenes like a man exiled for 50 years reuniting with his 100-year-old mother have competed on our screens with tales of torture and abuse from the prisoners streaming out of the “slaughterhouse” in Seydnaya. Thank God the Assads’ filthy linen has been exposed for all to see.

Blacklisted for years, I was able to slip into Syria seven times since the uprising began in March 2011, most recently as part of the Crazy Club, hiding under the cassocks of the clergy. Now I can return openly. The situation inside Syria is complicated and varies considerably from region to region but prices for most things have got cheaper and the Syrian pound’s exchange rate has stabilised. Embassies are re-opening, schools and universities have reopened and civil servants are back at work. In Damascus the hotels and restaurants are brimming, not just with journalists but also with foreign delegations – even from the US – queuing to offer support and investment. But water and electricity remain in short supply. As the architect living in my house explains: “They told us, ‘You were silently patient for 54 years, be patient for a few more days and you will have bright times to come.’ But it turns out we have no infrastructure. We still have electricity for only one hour in the day and one hour in the night.”

Even so, he is happy, along with my other Syrian friends, that they are starting the New Year without Assad. Turkey has taken on responsibility for repairing the airports, roads and trains while Qatar will get priority in the energy sector. The White Helmets, trained to dig bodies out from under the rubble of Russian and regime air strikes, are now redeployed to clear that same rubble left untouched by Assad for years.

None of Syria’s museums were looted during the lightning offensive led by the Idlib-based HTS. In fact, their government-in-waiting, now installed in Damascus with the same ministers in the same portfolios, reopened the Idlib museum after its priceless cuneiform tablets had been ransacked by the Assad regime’s soldiers. Assad posed as the protector of Syria’s cultural heritage, and claimed all his opponents were extremist terrorists, but when the rebels entered Damascus, historical sites like the National Museum and the al-Azm Palace were guarded. Sectarianism, too, was a narrative pushed hard by the Assad regime, yet in Idlib, al-Shar’a took care to foster positive relations with Druze and Christian communities, as he is doing now in Damascus.

Much of Syria’s cultural heritage, damaged across the centuries by fires, earthquakes and wars, has later been rebuilt, each time more beautiful than before. The Umayyad Mosque’s Jesus Minaret, added in the eleventh century, resembles a campanile, and is named for the spot where, according to local folklore, Christ will descend on the Day of Final Judgement, a blending of Christian and Muslim beliefs typical of Syria. Mary receives more mentions in the Qu’ran than in the New Testament, and Old Testament stories like Abraham and the sacrifice of his son form key festivals in Islam. Syrian Muslims have historically attended church services at Christmas and Easter with Christian friends, while mosques have welcomed those of all faiths and none.

The pressures are great and the future is precarious, but the Syrian people have the skills, the ingenuity, the innovative mindset and instinct for survival, despite the obvious deep trauma and hurt, to create a new Syria, one that may ultimately serve as a model for the wider Middle East.

[A version of this article was first published on 10 January 2025: https://www.thetablet.co.uk/features/rebuilding-damascus-the-liberation-of-syria/]

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA 5th century stonework carving [copyright Diana Darke]](https://i0.wp.com/dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-048.jpg?w=265&h=199&ssl=1)

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA The apse at Qalb Lozeh, 5th century [copyright Diana Darke]](https://i0.wp.com/dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-061.jpg?w=265&h=199&ssl=1)

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA What remained of the pillar of St Simeon Stylites, at the centre of the four basilicas in July 2010. [copyright, Diana Darke]](https://i0.wp.com/dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-067-st-simeons-pillar.jpg?w=191&h=254&ssl=1)

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA The chevet at St Simeon's Basilica, completed by 490. [copyright Diana Darke]](https://i0.wp.com/dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/damascus-trip-july-2010-073-st-simeon.jpg?w=339&h=254&ssl=1)

![20190426120125_01 Church of Bissos Ruweiha The Church of Bissos, Ruweiha, 6th century [copyright Diana Darke, February 2005]](https://i0.wp.com/dianadarke.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/20190426120125_01-church-of-bissos-ruweiha.jpg?w=265&h=177&ssl=1)