The Little Known Links between the Medieval Green Man, the Mystical Saint Khidr, and King Charles

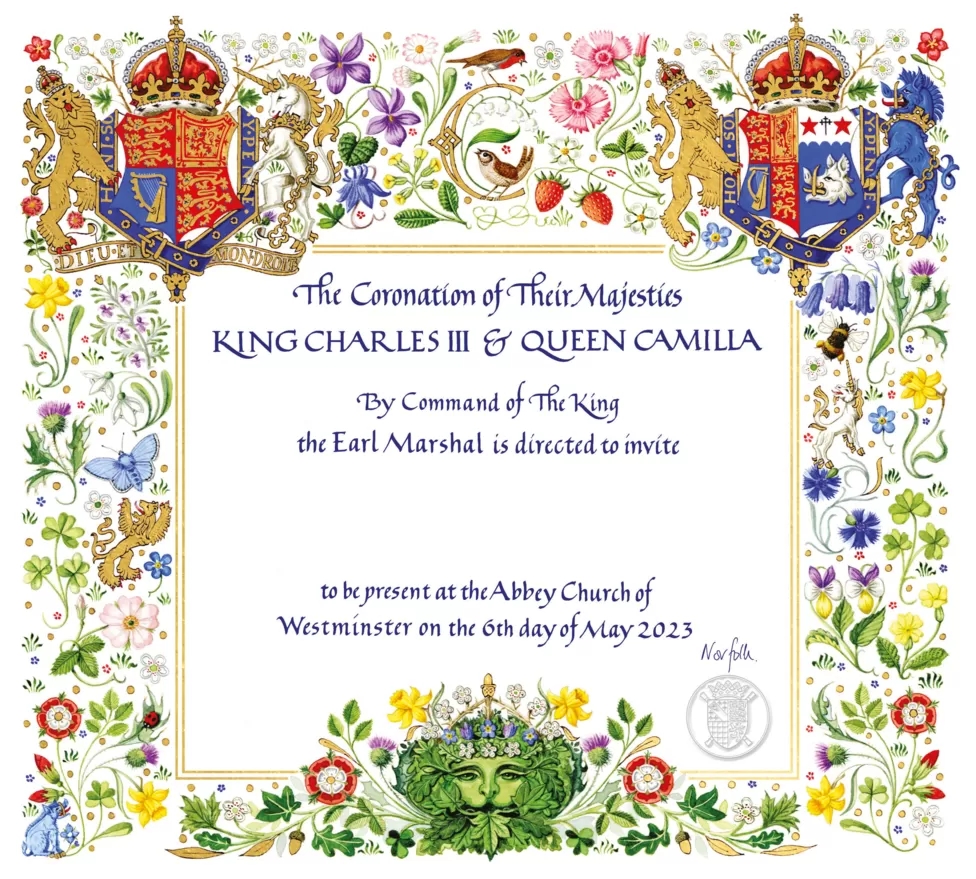

The colourful royal invitation to King Charles III’s coronation is rich with images of the natural world. It is a fitting reflection of the new king’s profound interest in nature and the environment. Prominently featured in the centre is what the BBC website calls ‘the folklore figure of the “green man” [https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-65175984], described by Buckingham Palace as ‘a symbol of spring and rebirth which celebrates a new reign’.

But what do people, including those at Buckingham Palace, really know about the mysterious Green Man? Seen peeping out from the carved foliage of so many Norman churches, he did not appear in England till the 12th century. His origins are shrouded in mystery and his meaning was lost by the end of the Middle Ages.

As part of research into the Islamic influences on Norman architecture, I have been studying the Green Man for some while now. The more I saw him, in all his moods, from menacing to humorous, from welcoming to ferocious, the more I saw his uncanny parallels with al-Khidr, a popular and well-known Islamic saint with many mystical associations. Al-Khidr means ‘The Green One’ in Arabic, and the Arabic root kh, d, r, conveys everything to do with greenery, green pastures, verdure and vegetation. The colour green was the Prophet Muhammad’s favourite colour, and al-Khudeira, one form of the Arabic root, means Paradise.

The timing of his appearance in our foliage and in this country, coupled with the fact that he was not known before, but appeared suddenly, suggests he was very likely brought back to England by returning Norman Crusaders. They would have first encountered him in the Holy Land, where he is deeply embedded in local folklore and Sufi mysticism as an omnipresent figure, a force for both good and evil. Given the powers with which al-Khidr is associated, his appeal to Christian Crusaders would have been considerable – it is not for nothing that he is conflated with St George, patron saint of England and, who, incidentally, is also the patron saint of the Lebanese Christians, the Palestinian Christians and the Syrian Christians.

There is however one big difference between al-Khidr and St George. Al-Khidr is still alive, whereas St George was martyred by pagan Roman soldiers and is well and truly dead. That said, like al-Khidr, he had the power to appear to people at moments of crisis and give them strength, as can be seen in the legend of his timely appearance at the 1098 Battle of Antioch, part of the First Crusade, riding on a white horse and carrying his famous lance, just in time to save the day and turn the battle in the Crusaders’ favour. It is a scene recreated in medieval church murals, as in the 12th century St Botolph’s Church at Hardham in West Sussex, painted by the monks of the powerful Cluniac Priory of Lewes. These monks, so associated with returning Crusaders, would have been entirely familiar with the legendary appearance of St George at Antioch, and his presence in the mural means it can safely be dated to the early 12th century, after news of the victory at the battle would have reached England. St George was especially venerated as a warrior saint from the Crusades onwards.

Church of St George, dating to 515, Ezraa, southern Syria

Al-Khidr’s immortality is a vital characteristic that he shares with the Green Man, whose various forms and facial expressions depict him as very much alive, like some kind of primeval spirit living among the foliage. Part deity, part prophet, part pagan, part saint, part human, his appeal has proved to be universal, a unifying figure among the three great monotheistic religions. In the Holy Land he is revered by Muslims, Jews and Christians alike, conflated not just as al-Khidr and St George, but also as the Prophet Elijah.

Of his many tombs, the most likely one to contain an actual body is thought to be in Lod, Israel, where the Crusader church of Saint George was built on top of an earlier Byzantine one alongside the Mosque of al-Khidr.

At Bait Jala near Bethlehem a shrine is believed by Christians to be the birthplace of St George, and by Hebrews to be the burial place of Elijah. William Dalrymple, in his book From the Holy Mountain, also came across this kind of syncretism and fluidity between religions in the Holy Land, writing of Bait Jala:

‘With all the greatest shrines in the Christian world to choose from, it seemed that when the local Arab Christians had a problem – an illness, or something more complicated – they preferred to seek the intercession of George in his grubby little shrine at Beit Jala rather than praying at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.’ He asked the priest at the shrine whether many Muslims came too, and the priest replied, “We get hundreds! Almost as many as the Christian pilgrims. Often, when I come in here, I find Muslims all over the floor, in the aisles, up and down.”

The shrine’s reputation as a place of healing was nothing new, but stretched back as far as anyone could remember, a continuous tradition. Such places carry a very special power and atmosphere.

My own first encounter with al-Khidr was in Aleppo, at a visit to the citadel in 1978, when I noticed his cenotaph to the right of the zigzag path that leads up through the succession of defensive gates into the citadel itself. Its location there was as if well-placed to give thanks, chosen for its survival of the dangers represented in the archway above the entrance by a pair of intertwined serpent dragons. Having navigated the fifth and final zigzag, with smiling lions and sad lions carved into the stone walls, seen as having magical powers and protecting against evil, you emerge into the sunlight of the open citadel summit.

These are exactly the properties with which the Green Man is credited today, in his many revivals in garden furniture and ornaments of the 21st century, the same powers with which he was credited in England from the Middle Ages onwards.

It is no accident that the oldest forms of him in England are to be found on early Norman churches, where his religious imagery shows itself in full flourish. The fact that he appears on doorways and entrances on the outside of churches, and again on the interiors, on chancel arches, capitals and columns, marking the transition into the holiest parts of the church, is not just coincidence. His role is to ward off evil spirits, to protect against harm, but also to celebrate the fertility of Nature and to welcome worshippers into the presence of God. He could be carved in wood or in stone, but was rarely to be found in illuminated manuscripts, stained glass or in jewellery. In the forms where his mouth, nostrils and sometimes even his ears and eyes, appear to be sprouting the foliage and vegetation, he also symbolises rebirth, the endless cycle of Nature of which he is an integral part. Often his face was the only sculpture to survive the obsessive destruction of the Reformation, presumably because he was not seen as idolatrous, but rather as a harmless representation of Nature that offended no one. This interpretation confirms that his origins as a saint were already lost to Christians by the 16th century.

The first Green Men to appear in England during the 1100s were the work of masons brought over from France after the Norman conquest in 1066. Their faces were not classical by any stretch of the imagination. The Green Men on the capitals of the main portal of Kilpeck Church in Herefordshire, for example, have protruding eyes with carved holes for pupils as found in early oriental statues of kings and pagan gods.

The Kilpeck foliage carvings also show Coptic/Fatimid style in the way the stems are bound together with ties and how the leaves have deeply incised v-shaped grooves.

At Barfrestone Church in Kent, sometimes called ‘the Kilpeck of the South’, a pair of Green Men on the north door likewise show no classical influence and are evidently protecting the church from evil spirits and may thus have given comfort and reassurance to a highly superstitious medieval population who would have wholeheartedly believed in evil spirits and their power. Sometimes, when smiling, he serves to welcome worshippers into the church.

The Gothic Revival brought the Green Man back into public consciousness and 20th century writers like JRR Tolkien in the Lord of the Rings introduced characters called Ents who were half tree half man, leading lives of quiet wisdom deep in the forest. Morris dancers are more versions of the Green Man, re-enacting old traditions that have been largely forgotten. He has well and truly entered the public imagination as an immediately recognisable figure, usually benign these days, but with occasional overtones of a wild spirit in league with nature. In this dual function and almost schizophrenic personality the Green Man again echoes the characteristics of al-Khidr. King Charles himself, I’d like to think, with his own freely acknowledged appreciation of Islam, would be happy to learn of such deep cross-cultural connections.

A version of this article was first published on Middle East Eye:

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/uk-green-man-islam-legend-mysterious