Spiritual Material: William Morris and Art from the Islamic World

Anyone familiar with Islamic art will long have known how heavily William Morris drew his inspiration from the Islamic world. One glance at his patterns is enough – the repetition to infinity, the twisting foliage, the richly entangled fruit and birdlife, the stylised designs that are often botanically impossible yet speak to us at some deep primordial level – all are hallmarks of Islamic art. Curiously, ever since his patterns were popularised, appearing in every imaginable accessory in our kitchens and living rooms, from curtains to coasters, from tablecloths to mousemats, those same iconic Morris designs have been subsumed as ‘quintessentially English’, somehow deemed to be an intrinsic part of our British cultural identity. It is the same blind spot that exists with Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame, proclaimed to be ‘quintessentially French’, synonymous with the French national identity, by those oblivious to the Islamic origins of such rich architectural styles and ornamentation.

Until, that is, it is pointed out in exhibitions like ‘William Morris and Art From the Islamic World’, still running till 9 March 2025, where the eye can become trained. All credit is due to the William Morris Gallery, the fine Georgian family home in Walthamstow where Morris grew up, for staging this exhibition, and for highlighting to a British audience what has been hiding in plain sight all along. The gallery’s guiding mission has been to bring the communities of Walthamstow, where one in five of the population is Muslim, closer together, an outreach project to show how different cultures have intertwined and inspired creativity since time immemorial. Maybe a future exhibition at the V&A could do the same for Islamic architecture and European medieval styles like Romanesque and Gothic?

The starting point of the exhibition is a smallish room which brings together items from the Islamic world all of which, crucially, once belonged to Morris and his family. Though Morris himself never travelled further east than Italy, he acquired a range of carpets, textiles, metalwork and ceramics mainly from Iran, Syria and Turkey, which clearly served as his prototypes, using them to decorate his homes. This geographic range is very important to the curators’ careful and deliberate choice of phrasing in the title ‘Art from the Islamic world’, a much more accurate description than was common in Victorian times when all Islamic art was labelled ‘Persian’, considered the ultimate in Orientalist chic. Even today, museums like the Jackfield Tile Museum in the Ironbridge Gorge perpetuate such misnomers in their labelling, describing English tiles that are clearly copying Ottoman Turkish tile designs as ‘Iranian-influenced’.

When Morris, who often railed against the privileged society into which he was born, first launched his business in 1861, opening an interior design shop in Oxford Street, he was trying to bring his styles to the middle classes, well aware that most of his commissions were for wealthy clients with more money than aesthetic sense. ‘I spend my life ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich,’ he lamented. Some mocked his hand-made approach to design and craftsmanship as ‘thoroughly medieval’ and ‘useless’. At the time, his style of artist-led designs, using quality materials and hand-craftmanship was pushing against the tide of the Industrial Revolution. ‘I have never been in any rich man’s house,’ he declared, ‘which would not have been the better for having a bonfire made of nine-tenths of all that it held.’ It was part of his ‘Crusade against the age’, and in the end his persistence prevailed, for by the turn of the century, Morris & Co had become a by-word for good taste. He sold to important clients in Europe, America, Australia and Canada, exhibiting at international trade fairs in Paris, Boston and Philadelphia to raise the company’s profile. He learned to be a businessman, buying out his partners, and extending his product range to more affordable off-the-shelf items like wallpapers, fabrics and tiles. The Arts and Crafts movement, spearheaded by Morris, began in England and flourished in Europe and America between 1880 and 1920. On his death aged 62 in 1896 his coffin was draped in a magnificent 17th century Ottoman brocaded velvet from his own collection, made from silk and metal thread in Bursa, the first Ottoman capital.

Regret that his products were beyond the reach of the ordinary working class contributed to Morris’s growing political activism. Acutely conscious of his own privileged status in high society, he denounced the increasing industrialisation of the time, and became a socialist aged 50. He criticised the British government’s attempts to drag the country into a Russian-Turkish war in 1877, warning against ‘false patriotism’ and the dubious motives of the ruling classes who were led only by desire for profit.

Becoming a fervent environmentalist, he descried the despoliation of the landscape, and fought to stop pollution of the Thames and the destruction of Epping Forest. Although a nervous public speaker, his belief in his cause led him to give up to a hundred lectures a year, sometimes three a week, determined to make a difference. Driven by idealism, he wanted to imagine a world in which communities were equal, with no concept of private property, where craftsmanship and creativity could flourish. In 1877 he founded SPAB, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and led the campaign to save the west front of St Mark’s in Venice. He was also outraged by the appalling restoration of St Albans, where the new pseudo-Gothic west front damaged much of the original fabric.

In south London at Merton Abbey, the Gothic ruins of which he restored, along with its water mill (another innovation introduced to Europe from Syria via Islamic Spain) on the River Wandle, he recreated an environment of medieval craftsmanship and techniques. He used natural dyes like indigo, disliking intensely the synthetic dyes of the times, even though it took him ten years of experimentation to achieve good results. So smitten was he with the beauty of Persian and Turkish carpets, hanging them on his walls or draping them over his tables as far too precious to walk on, that he decided to pioneer the production of hand-made rugs in Britain, recruiting experienced weavers from the declining Spitalfields silk industry, and using specially-built hand looms, hoping that eventually their skills would pass down to the next generation so that Britain might build its own hand-woven carpet tradition. One such example, called ‘Peacock and Bird’ is on display in the exhibition, so strikingly inferior in workmanship to the real thing that it serves as a clear marker that, even with the best will in the world, and the money, such traditions take centuries to accumulate and evolve.

All Islamic art ultimately seeks to recreate Paradise in the form of gardens and rivers, flowers and trees, where hierarchy is absent and where all live peacefully in mutual cooperation. The material and the spiritual world are connected through geometry, the unifying intermediary. This is precisely what Morris the idealist clearly felt drawn to in Islamic art, with its egalitarian traditions and deep respect for nature. As a child he had loved observing birds, flowers and plants in the Essex countryside. One of his most sophisticated patterns, which he named ‘Rivers’, after tributaries of the Thames, is based on meandering diagonal stems and natural growth, so that, as he put it, ‘even where a line ends, it should look as if it had plenty of capacity for more growth.’ This, together with his use of stylised birds and animals in pairs, to give underlying geometric structure to his patterns, are further borrowings from Islamic art. Other motifs he used, like flowers in vases, are also common in Islamic art.

Granada, the most technically complicated textile Morris ever produced, so complex it never reached commercial production, was woven in 1884 at Merton Abbey. Featuring pomegranates and almond-shaped buds, connected by pointed arches and branches, the name tells us that his inspiration came from the patterns of the Alhambra Palace of the Nasrid kings. Though Morris himself never visited the Alhambra, he knew it through the lens of designer-architect Owen Jones (1809-74), who spent six months at the end of his Grand Tour, aged twenty-five, drawing detailed sketches of the stucco wall patterns of the palace, and acquiring a fascination with geometry, colour theory and the use of abstraction in decorative ornament. The result was his seminal work The Grammar of Ornament (1856), still used as a sourcebook in design schools internationally.

As the Gothic Revival got underway, the wealth generated from industry and trade, together with religious reform, resulted in a frenzy of churchbuilding, leading Morris to enter the market for church furnishings, like stained glass, embroidery, furniture and metalwork. Many of Morris’s contemporaries shared his interests and beliefs, like stained glass designer and tile-maker William de Morgan who also joined the Arts & Crafts movement. De Morgan moved his business to Merton Abbey, where he reproduced the fourteenth century ‘lustreware’ techniques of Muslim craftsmen, inspired by Islamic and medieval patterns. His tiles also decorate the walls of Leighton House in London’s Holland Park with its famous Arab Hall, a showcase of original sixteenth-century Damascus tiles procured on behalf of the painter Lord Frederic Leighton (1830-96).

A separate room in the exhibition is devoted to Morris’s daughter, May Morris, who travelled to the Islamic world after her father’s death. It displays the various items, especially textiles, she brought back and clearly valued highly, becoming a collector herself, as well as a donor.

A beautifully illustrated book, titled Tulips and Peacocks in a nod to the most prized flower of the Ottoman Turks, and the most loved bird of the Persians, has been published by Yale University Press specially for this exhibition, featuring a collection of ten essays by different specialists, including excellent contributions from the exhibition’s curators, Rowan Bain and Qaisra M. Khan, each exploring aspects of Morris’s connections to Islamic art. The front cover shows the distinctive 17th century Damascus tiles that Morris had acquired, in a pattern he called ‘Vine trellis’, purchased by Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum after his death, and now reloaned by the Fitzwilliam for display at this exhibition. The book is on sale in the gallery’s shop, along with an impressive array of Morris-themed memorabilia for gifts or souvenirs.

Morris believed that through his work he could act as a bridge allowing craftspeople of the past to pass on their knowledge to contemporary artisans. The enduring popularity of his patterns suggests this may have been no idle dream, as people continue to respond to the same quasi-mystical, other-worldly qualities in his designs which echo those of Islamic art. Just below the surface, there is always the sense that something divine, something bigger than us mere mortals, unites us in our humanity. In this, perhaps, lies Morris’s universal appeal.

[A version of this article first appeared in The Times Literary Supplement (The TLS) on 17 January 2025]

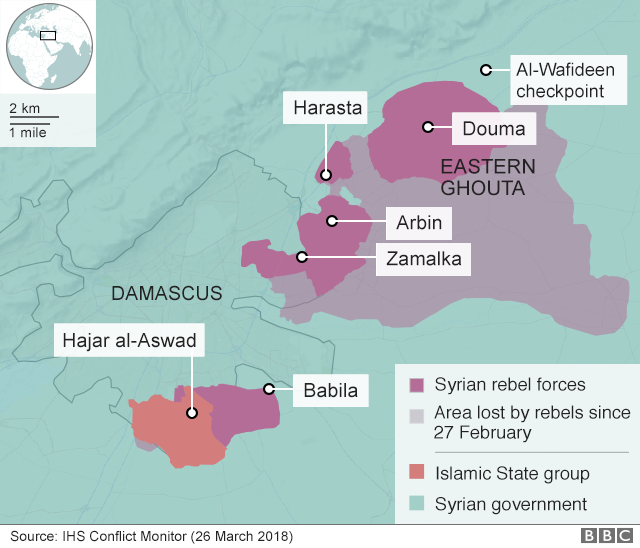

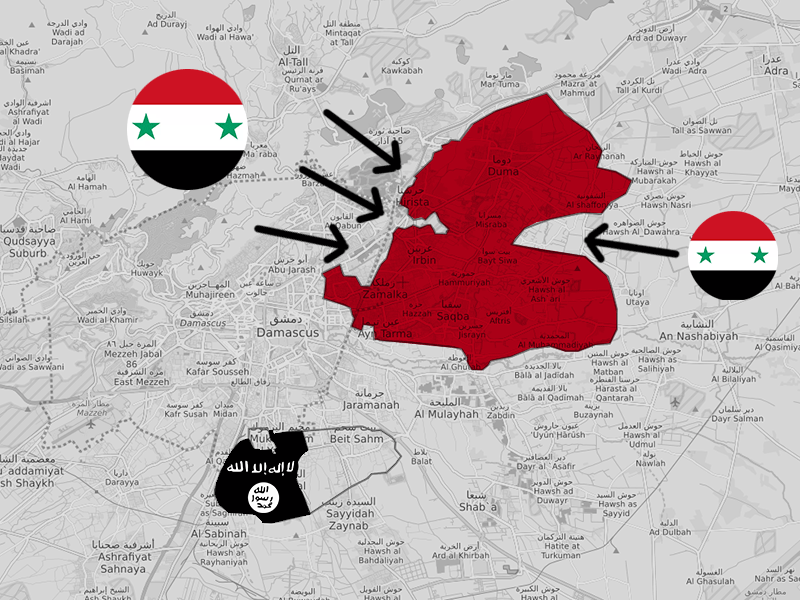

When a country has been at war for over five years, it might seem natural to assume that all cultural life is suspended. In the case of Syria, this is far from true. But just as with the war itself, there are many levels and layers to be unravelled, and the definitions of “culture” vary according to who, and where, you are.

When a country has been at war for over five years, it might seem natural to assume that all cultural life is suspended. In the case of Syria, this is far from true. But just as with the war itself, there are many levels and layers to be unravelled, and the definitions of “culture” vary according to who, and where, you are.